From Goinvo.com by Sharon Lee, GoInvo and Jen Patel, GoInvo

We spoke to leading experts in the field and borrowed best practices on the management of patient health information (PHI) to outline an open and ethical approach for designing patient-centered, meaningful consent. The wisdom and guidance of Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, Joyce Lee, Ernesto Ramirez, Gabriel Martinez-Santibañez, Charles Schick, and Woody MacDuffie helped immensely on this journey.

Background

What is Informed Consent?

“Informed consent: The process by which a patient learns about and understands the purpose, benefits, and potential risks of a medical or surgical intervention, including clinical trials, and then agrees to receive the treatment or participate in the trial1.”

At a baseline, meaningful consent requires2:

- informedness

- comprehension, AND

- voluntariness

Consent materials should cover both benefits and risks of participation2.

When patient health data is involved, meaningful consent should also effectively communicate3:

- how patient data will be used,

- who will have access,

- how it will be protected, and

- what rights the patient has over the shared data.

The gap in comprehension

Informed consent is especially important in medicine and health related services. Patients need to adequately weigh the pros and cons of their involvement to make the best choice for their health. Unfortunately, three issues with traditional consent can prevent patients from fully understanding what they are agreeing to.

- Consent documents are usually filled with complex legal language4.

- The consent process is usually rushed4.

- It has become the norm to accept documents without fully understanding them. The documents themselves are usually not designed with a focused effort to promote patient understanding4. One group of researchers found that over 90% of adults agreed to a terms of services and privacy policy that included multiple ‘gotcha clauses’ including “providing a first-born child as payment for SNS access5“.

- Comprehension is rarely measured. In other words, most consent processes don’t track what patients understand.

An opportunity for re-design

Pew Research Center found that 77% of Americans have smartphones as of 20186. Despite this, many patient consent processes are still filled out on paper. From a survey conducted in 2017 with 146 respondents from top biotech, pharma, CRO, and IRB organizations, 53% reported their organizations still didn’t use electronic consent7.

Paper consent often requires extra steps of downloading PDFs, printing, signing in separate software, and then scanning, mailing, or emailing it in. A mobile consent process allows patients to work through consent whenever and wherever they want2. It allows them to complete the consent process in their own time, supports the patients’ future reference of the agreement, and can allow patients to manage or revoke their consent as the terms allow.

As researchers, healthcare providers, and healthcare companies shift to eConsent, a few researchers have explored best practices for their design. Groups, including Sage BioNetworks and AllofUs, are pushing the needle away from lengthy, complex terms and conditions and towards truly meaningful consent.

We hope that this list of guidelines to improve patient comprehension can help to inform eConsent design.

9 Guidelines for eConsent Design

1. Meet Accessibility Standards

At the most basic level, the consent process must meet the needs of those with disabilities (see WCAG2.1 guidelines).

2. Make Consent Front and Center

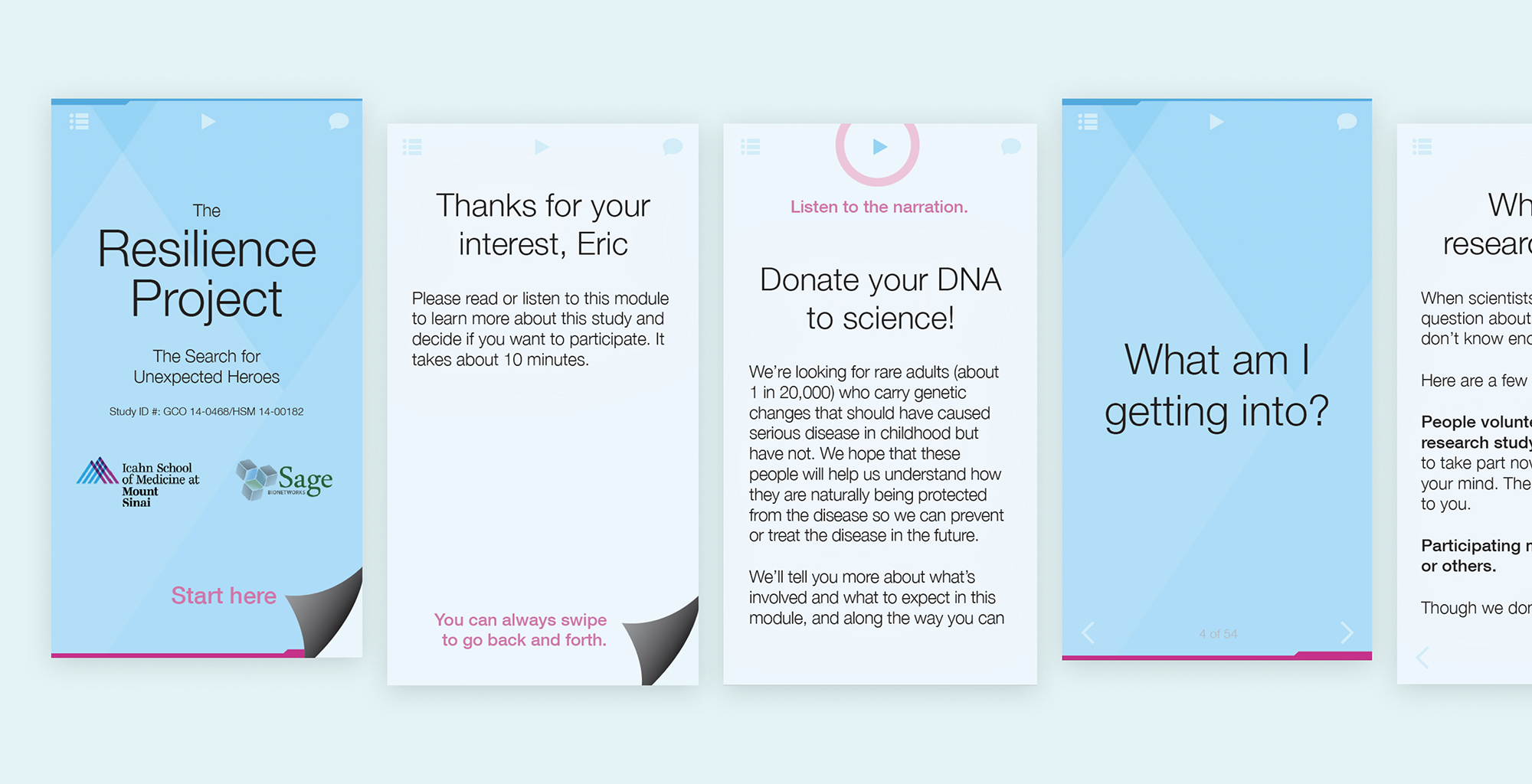

The gateway to involvement in the Resilience Project is a 10 minute screening + consent process (Goinvo designs with Mount Sinai and Sage Bionetworks from 2015).

Beyond this, we must remove other barriers to access, such as burying consent documents under numerous links or only supporting paper consent.

3. Use Plain, Concise Language

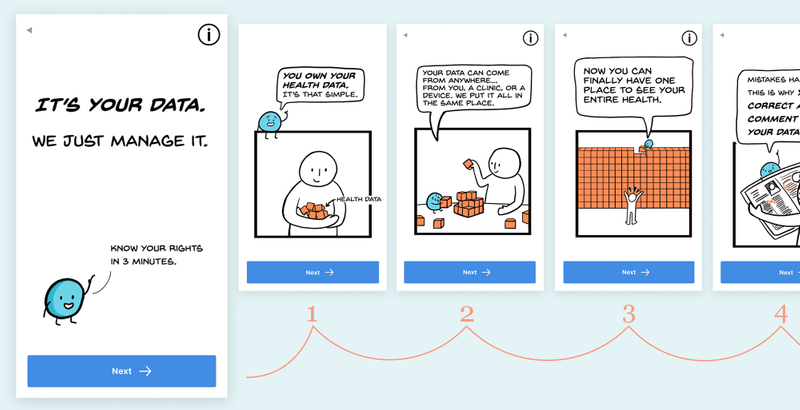

These initial designs for (Patient Health Data Manager (an opensource project by MITRE and GoInvo) use familiar language and a non-intimidating format.

Legalese can sound like a foreign language to patients. Plain, concise language can be read quickly and understood, making it more accessible8. Plain language should be at or below a 5th grade reading level in order to support the comprehension of those with low literacy9.

4. Set Time Expectations

Consent can feel like an endless stream of content. Cue patients in on how long it will take them through a comment at the start, a progress bar, or other. This allows patients to evaluate whether they currently have enough time to complete the consent process and can help prevent patients from rushing to the end.

5. Organize Content into Bite-sized Sections

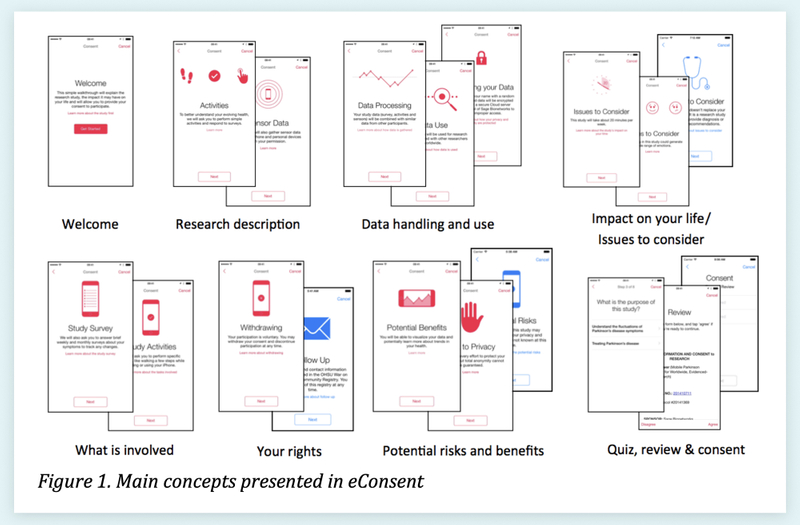

Above is Table 1 from “Developing a transparent, participant-navigated electronic informed consent for mobile-mediated research,” which illustrates how sections can be paired down to their essence and organized by topic10.

In a “novel multi-media approach to addressing transparency and comprehension within electronic informed consent,” Sage Bionetworks suggest focussing on the essential and organizing content deliberately10. Breaking the consent document into bite-sized, topic-focused chunks can help the participant better grasp the sections. Keeping content succinct can help prevent the reader from skimming.

6. Use Visual Storytelling

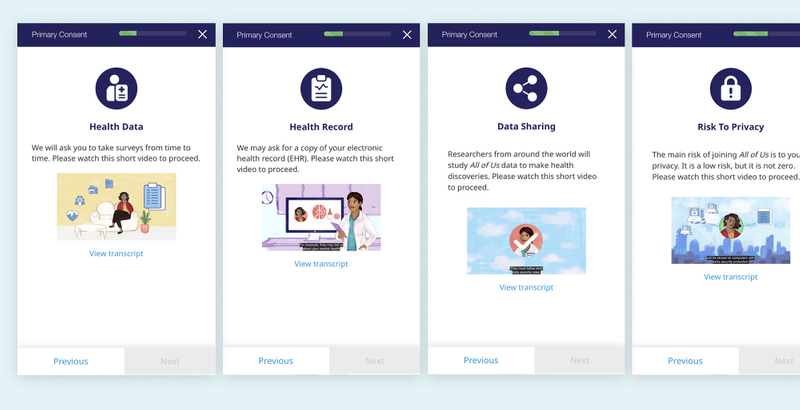

Above are select screens from the AllofUs consent process, which uses animated and narrated videos to inform the patient.

Humans are visual and aural communicators. Adding straight forward icons, illustrations, animations, or even videos can help to engage the reader. Visuals serve as a memorable indicator of topic that can help bolster understanding10. One research group found that using friendly comic strip visuals improved “patient comprehension, anxiety, and satisfaction11.”

7. Provide Real-Time Help

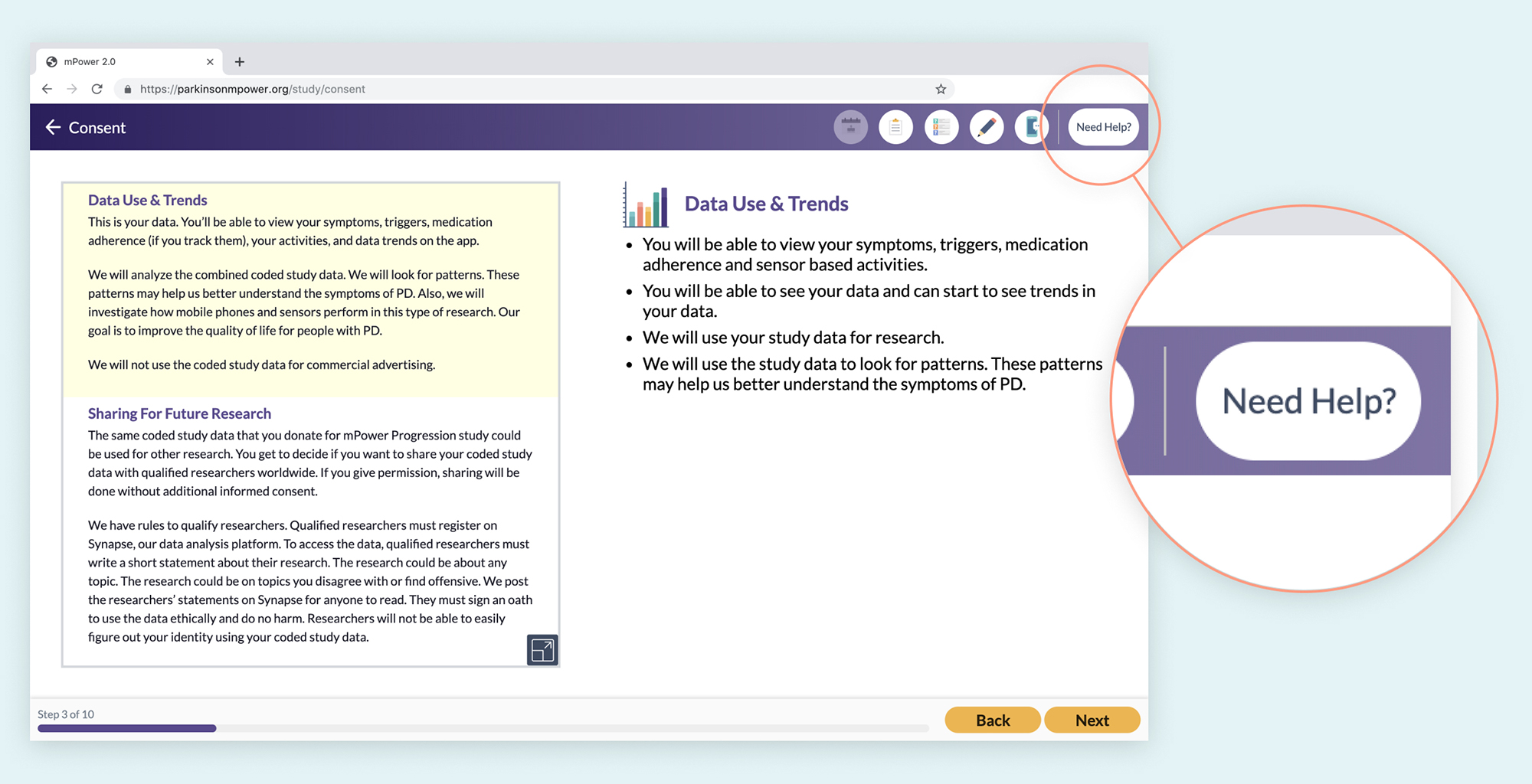

The mPower consent process features a “Need Help?” button throughout the entire consent process. It provides the patient with a thorough FAQ section as well as a toll free number for additional support.

Supporting comprehension takes more than just clear wording and accessibility. It means providing help and resources to patients when and where they need it. Resources and support can take many forms such as a ‘Learn More’ or ‘Help’ button, a support chat, a toll-free phone number with a helpful human resource on the other end, and more10.

8. Use “Repeat Back” to Engage the Brain

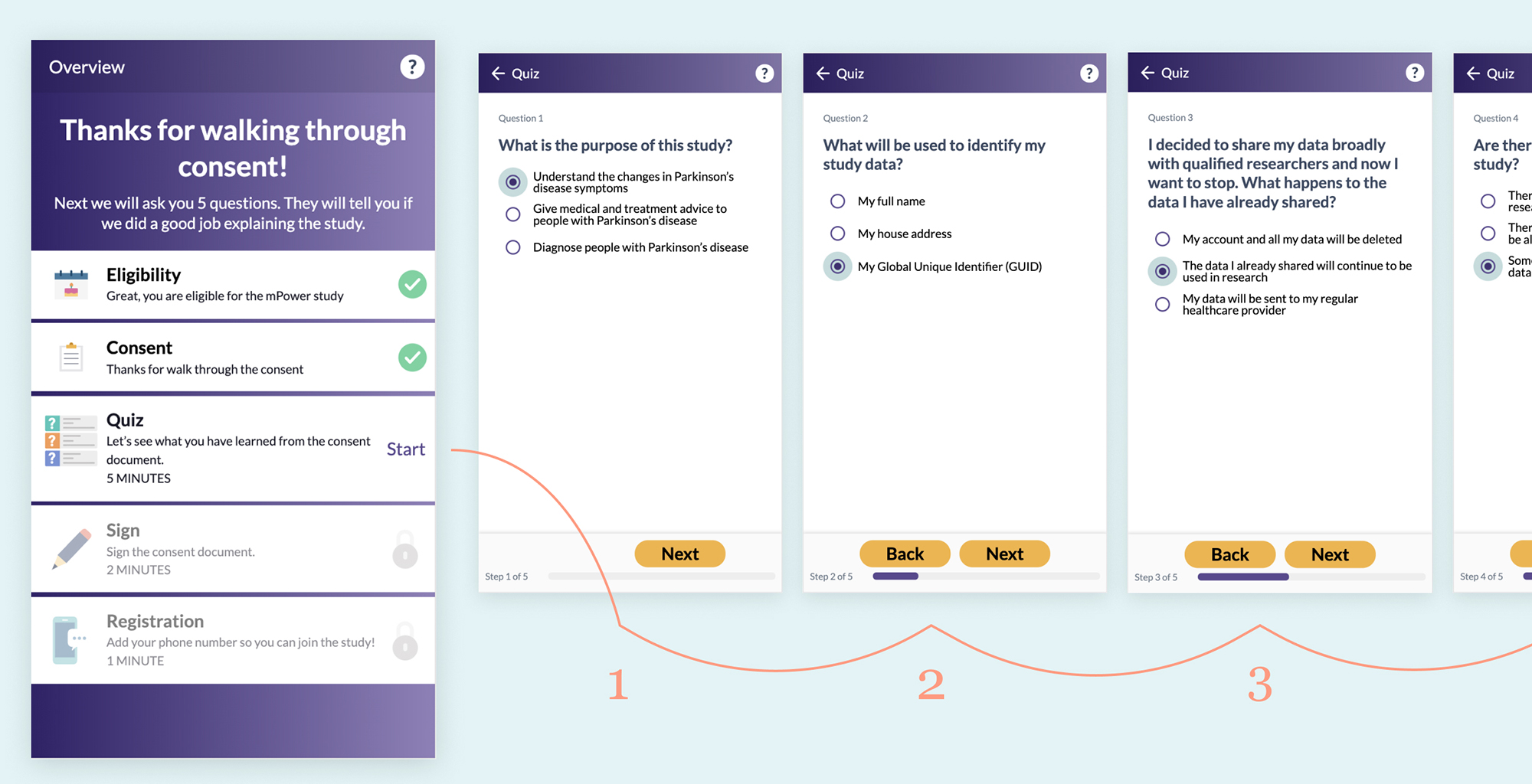

After reviewing the consent documents but before signing, the mPower consent process gives the patient a short 5 question quiz.

The National Quality Forum developed an approach called Safe Practice 10 with in-person patient consent to improve comprehension. Part of this practice includes a “teach back” or “repeat back” technique where the patient is asked to recall primary details from consent that has just been discussed with them. Multiple studies have found that having the patient recall the information improves comprehension12. Similarly with eConsent, a short quiz can help engage the patient’s mind in a new way and help them retain the major takeaways of the agreement.

Bonus: 9. Keep Measuring + Iterating!

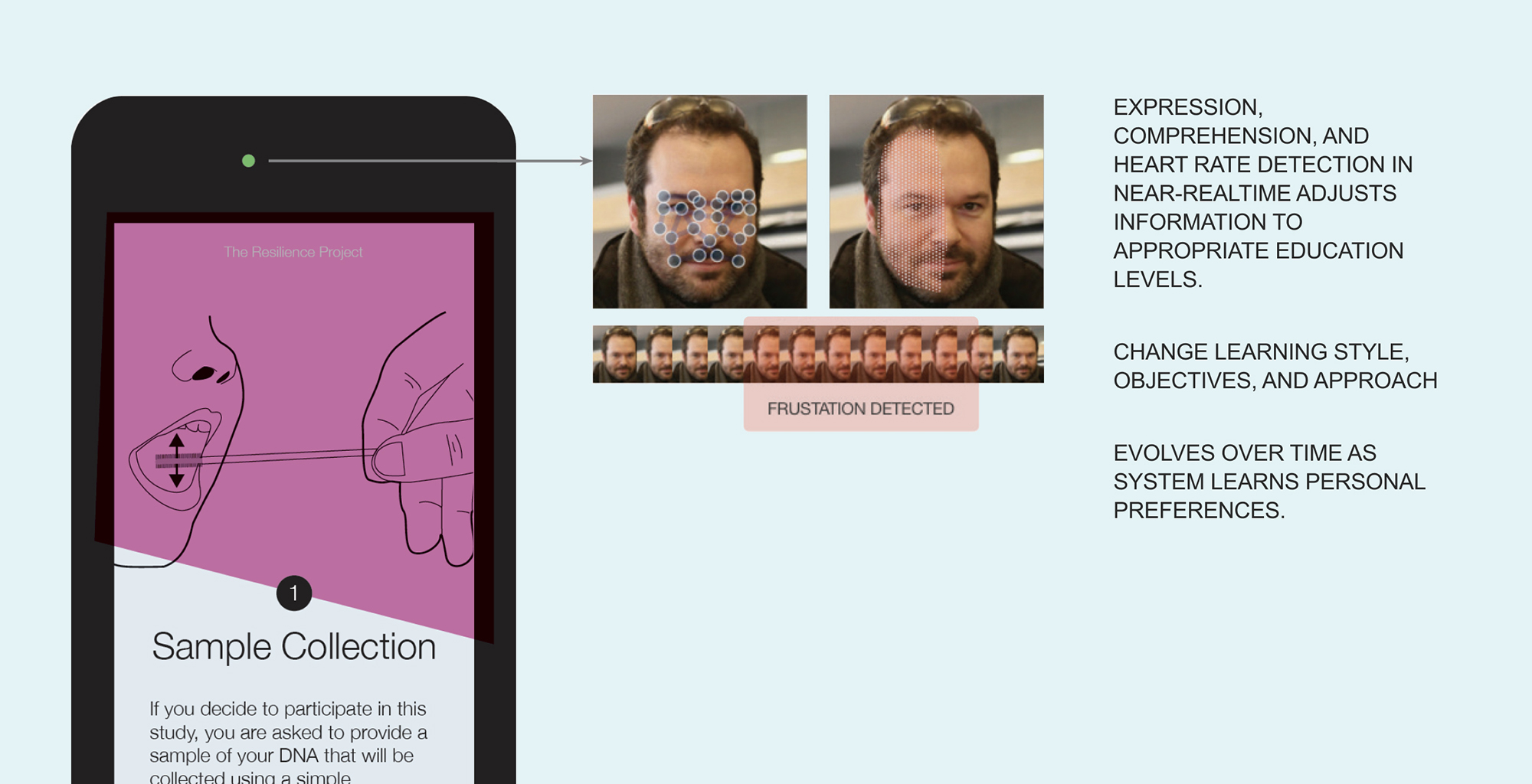

A concept explored to adjust content and interaction in real-time based on facial expressions (from our Resilience Project designs).

There is always room for improvement in consent design. Before releasing the consent process, set lofty goals for your designs and test them with representative users. Are users able to answer questions on the primary consent take-aways after going through the process? After releasing your consent process, are there systems in place to continue receiving feedback and measuring comprehension?

Recap

- Meet Accessibility Standards

- Make Consent Front and Center

- Use Plain, Concise Language

- Set Time Expectations

- Organize Content into Bite-sized Sections

- Use Visual Storytelling

- Provide Real-Time Help

- Use “Repeat Back” to Engage the Brain

- Bonus: Keep Measuring + iterating!

Authors

CONTRIBUTORS

References

- Jr, W. C. (n.d.). Definition of Informed consent. Retrieved June 18, 2019: https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=22414

- Doerr, M., Truong, A. M., Bot, B. M., Wilbanks, J., Suver, C., & Mangravite, L. M. (2017). Formative Evaluation of Participant Experience With Mobile eConsent in the App-Mediated Parkinson mPower Study: A Mixed Methods Study. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 5(2). doi:10.2196/mhealth.6521: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5334514/

- Patient Consent for Electronic Health Information Exchange. (n.d.). Retrieved June 18, 2019: https://www.healthit.gov/topic/patient-consent-electronic-health-information-exchange

- Wilbanks, J., B.A. (2018). Design Issues in E-Consent. J Law Med Ethics. doi:10.1177/1073110518766025: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6062847/

- Obar, J. A., & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2018). The Biggest Lie on the Internet: Ignoring the Privacy Policies and Terms of Service Policies of Social Networking Services. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2757465: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486870

- Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States. (2019, June 12). Retrieved June 18, 2019: https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- State of eConsent 2017 Report. (n.d.). Retrieved June 18, 2019: https://resources.crfhealth.com/electronic-informed-consent/state-of-econsent-2017-report

- White House Precision Medicine Initiative. (n.d.). Retrieved June 18, 2019: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/precision-medicine#section-principles

- Communicating with Patients Who Have Limited Literacy Skills. (1998). The Journal of Family Practice, 46(2), 168-175. Retrieved June 18, 2019: https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/jfp-archived-issues/1998-volume_46-47/JFP_1998-02_v46_i2_communicating-with-patients-who-have-lim.pdf

- Doerr, M., Suver, C., & Wilbanks, J. (2016). Developing a Transparent, Participant-Navigated Electronic Informed Consent for Mobile-Mediated Research. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2769129: https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=722009025090070117080012101085114002000071009031061037125097088119009102109102119101099038107061010025028092092080122065098105007010093003076112103109116006085100029057035000100077107084125011002065028029127126094079096086083107104089069097105001078017&EXT=pdf

- Brand, A., M.D., Gao, L., M.D., Hamann, A., Crayen, C., PhD, Brand, H., Squier, S. M., PhD, . . . Stangl, V., V. (2019). Medical Graphic Narratives to Improve Patient Comprehension and Periprocedural Anxiety Before Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(8), 579. doi:10.7326/m18-2976: https://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/2730521/medical-graphic-narratives-improve-patient-comprehension-periprocedural-anxiety-before-coronary